A Bit of Rambling

The art of peoples like the Legas and Lubas and other Eastern Congo tribes has been discovered later than, for example, the art of the Baoule in Ivory Coast, or the Kongo art in Western Congo.

Access to this part of the world by Europeans is more recent than in areas closer to the sea.

The Christian religion influenced the lifestyle and the art of the peoples in the west of what is now RDC, much before they influenced those of Eastern Congo.

Even today some Lega old men have never seen a white man! Because of the difficulty to access some remote areas of the Lega land. No road, just walking trails.

Like in Europe, the Art of the African peoples was mostly created for religious/spiritual and social reasons. The arrival of the Christian priests with the colonial powers has had a very destructive impact on the local culture and art.

Kenya is an example in kind since most of its traditional art has been burned on the request of the church.

Eastern Congo, because of its isolation has escaped this destructive period.

When African Art was discovered by European artists like Picasso, Vlamink, Modigliani, Matisse, and others at the beginning of the 20th Century, this changed completely the approach to traditional African Art. The first religious men coming to Eastern Congo were in fact the first collectors, followed by the Belgian colonial administrators! The objects which were collected then, and taken to Europe or the US are now worth big money. Those are the pieces which are sold by the big Auction Houses.

But in Eastern Congo, it occurred much later than in Gabon for example where the Fang Art production has been admired since the beginning of the 20th Century in Europe.

We can say that the Art of the Legas and Lubas, Hembas and other Eastern Congo Tribes has really been discovered in the 1930’s to 50’S. The Senegalese rabatteurs who came first in the 1960’s and 70’s exported a lot to Europe via Nairobi, Bujumbura or Kinshasa. This is when scholars started to really discover and classify the art production here.

Copies obviously came close behind, but first produced by the same artists who made the real traditional art. So the distinction between pieces which were made for rites, and those made for foreigners is somewhat fuzzy.

Today there is a real industry of fakes, made in Cameroon or elsewhere, but it is usually possible to distinguish between fakes and the real thing, because of mistakes in the style or the material used, or because of the patina.

However, to complicate things even more, there are sometimes divergences of opinion between the experts in Europe and the collectors today. Indeed, the experts are very careful not to risk to declare an object good when in fact it is a copy.

So when they are not sure, they tend to say that it is not good!

The problem is that they do not know everything, and for example there are over 3000 different types of Lega objects, probably the most varied African Art production. The experts may be tempted to declare that a piece is a fake when in fact it is a rare type of object.

Furthermore African Art pieces which have stayed 50 or more years in their original environment in the villages of East Africa are often in bad shape. Some are eaten by bugs, some are dirty, some have a smell of smoke after staying for years near a fireplace. (Now fake makers manage to imitate this with some success). While the objects which moved to Europe 50 or more years ago have been cleaned, kept in dry places, so they have been maintained in good condition. They age much better than the ones which have remained in the village, and for some of them it really shows and can be confusing.

The objects that you will see here have not been sent to Europe or the US. Most of them date from the first half of the 20th century or up to the 1950’s, and if we know more about the age or the provenance, we indicate it.

For many of them their history has been complicated.

Some of them may have been looted by the Congolese Army or by the Mai-Mais, or even possibly stolen from the museums which were created at the time of Mobutu, But since there were no records except for the Kinshasa Museum, we may never know.

Some have been collected by Europeans and then confiscated when things became tough for Europeans in Zaire.

Many have been kept by the families of the late Army members or other Congolese, and those trickle down to Nairobi or Europe even today.

Finally there are 2 collectors in Kenya who have kept a stock of pieces collected in the 1980’s and are selling some now.

But what we can certify is that they are not recent copies. We give an example of the difference between two objects.

Concrete Example

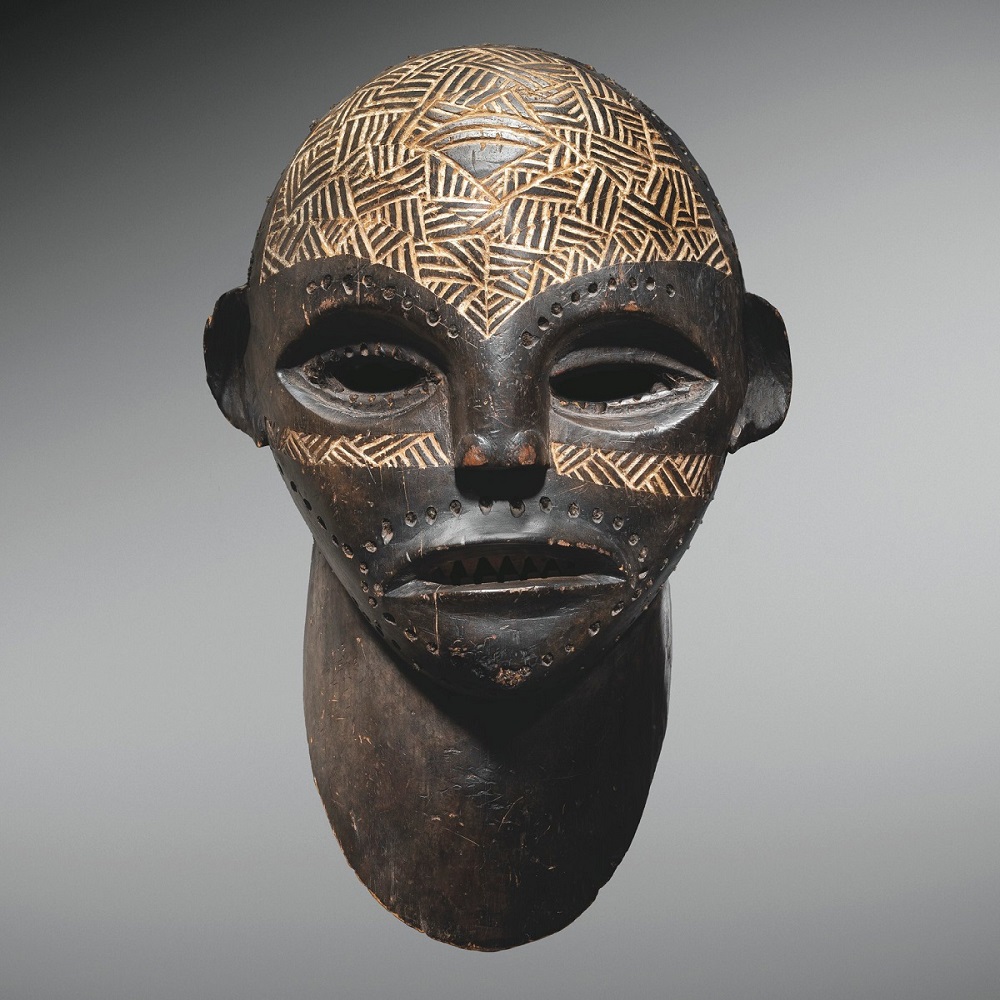

This very famous luba mask of a “homme fauve” ( a possible translation would be “lion man”) has a little brother! The attached photos demonstrate that the same sculpteur did (at least) two of them. One was taken to Europe long time ago and went into the most prestigious collections, was very well maintained, even possibly restored. The second one, a bit smaller, which may have been done to replace the first one, is in the collection of JFD.

JFD is convinced that it is not an elaborate copy for two reasons:

First the overall condition indicates that it was poorly maintained, probably left in some kind of bag with other objects, and it stayed unattended for years. It would be difficult for a fake maker to copy this type of poor maintenance. They can do termites damage, they can leave an object for a year or two in sand with goats above providing dampness… They can do a few other tricks, but a regular aging without maintenance, and without major damage, would be difficult to imitate.

But the main argument is the hairs. The “homme fauve” described in the monography by Julien Volper, under fig. 11 has holes around the eyes and many other places where hairs were implanted. Those hairs, or fibers of some kind, may have rotten with time or started to fall, and they have been cut, or rather burned, at the level of the wood surface (see attached photos).

The same thing is found on JFD’s piece. He doubts that any fake maker in his right mind would take the time, and have the skill to put the hairs in place and then cut them!

In addition, some of the designs are similar, not identical, like for example the lines on the forehead and the cheeks, as if the sculpteur remembered the first mask but not all the details.